On (Not) Photographing Protests

The past decade has seen several major protests and liberation movements form in the United States. There’s an undeniable need and appeal to document these moments in a variety of media. Unfortunately, the visual documentation of this, particularly the documentation of legitimate expressions of rage and frustration, can be used to identify and harm those involved. In the years following the uprising in Ferguson, MO that helped kick off the Black Lives Matter movement, six people involved died mysterious deaths, leaving activists to speculate on the role of dramatic protest photography in making them identifiable. This year, the FBI and Philadelphia police used a variety of protest photos to identify a person accused of burning a police car.

This has sparked a conversation about the role photographers (including photojournalists) should play in documenting these events. One easy solution, particularly since masking laws are not being enforced due to the Coronavirus outbreak, has been to not show people’s faces. One photojournalist has decided to curate the photos they share in an effort to protect protestors by not sharing photos where faces are visible. This is a good start, but in the Philadelphia case it was a t-shirt and a tattoo, not a face, that lead to arrest, leading for a more general call for people to refrain from taking any pictures at all or to generally consider how to do so safely and responsibly by hiding faces and scrubbing metadata. All of these are good ideas, including encouraging (most) people not to take photographs. For Black photographers, however, photography allows for a control of a narrative history that has long been denied to Black people in general. As a white person, I’m certainly not going to tell Black people not to photograph events significant to their own history and as a white photographer I would like to use some of the privilege afforded to me to contribute to that storytelling.

What follows are some thoughts and my own personal considerations for photographing protests. It’s ultimately going to be up to individuals to decide for themselves how to approach a given situation. I draw on my experience in ethnography and the ethical considerations of protecting your collaborators’ rights in doing academic research and writing. Visual ethnography often falls severely short of this in practice, but the general rules guiding anonymization are good. I’ll also include some of my own photographs and my justification for sharing them. I’m certainly open to discussing these further and my views are ever-changing.

First, we shouldn’t fully relinquish the right to photograph (or video) events. The below photos were taken at various protests in Brooklyn and show police officers and suspected white supremacists taking photos and video of protestors. We’re not going to be able to stop them so long as they exist, so by relinquishing all power of visual storytelling we’re leaving it in the hands of people who are against us. Instead, we should document it ourselves and have our own version to share.

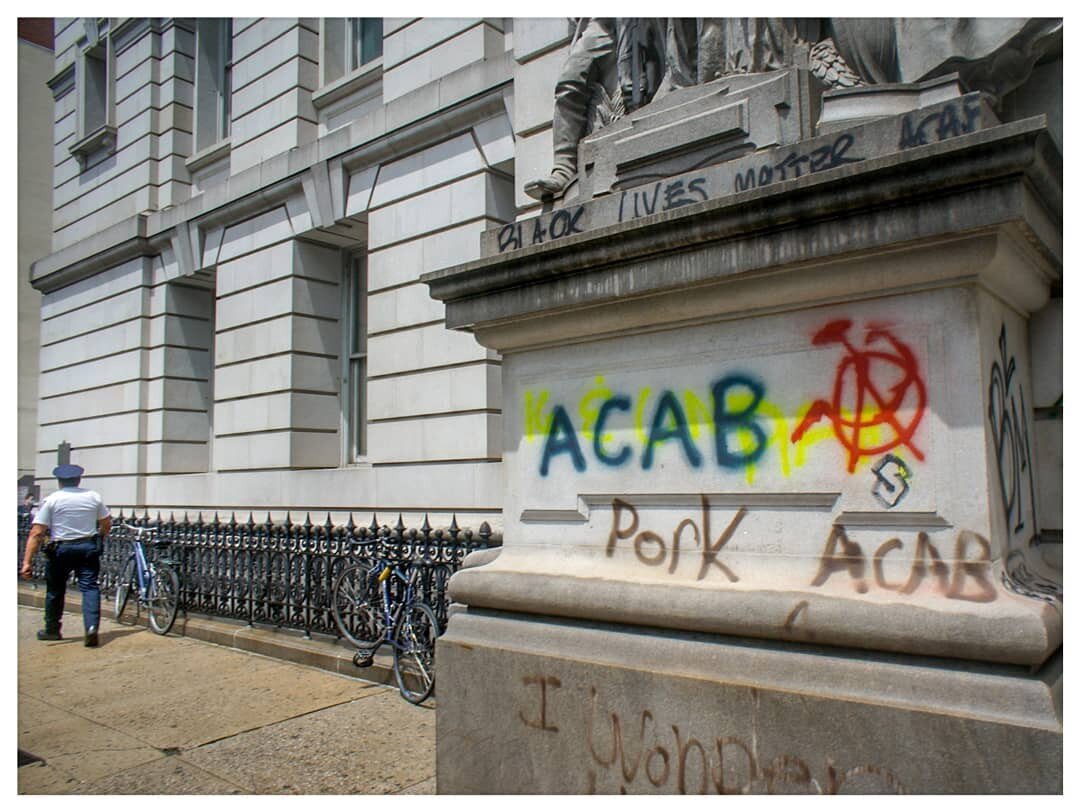

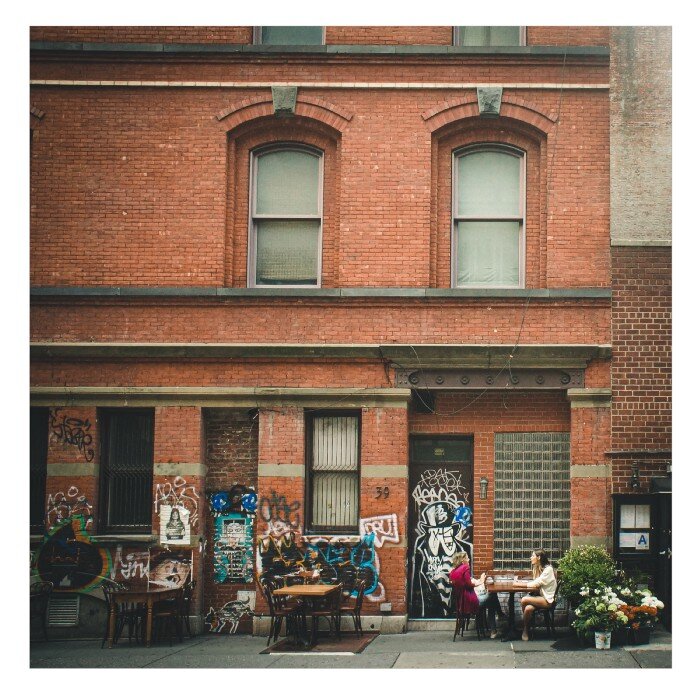

However, documenting protests for ourselves is dangerous. There’s no denying that but there are ways to mitigate it. First, by not showing who else was there. It’s always going to be obvious that we, the photographer, was present and thus we should be on our best behavior, but we can take photos that show the protest that don’t include identifiable individuals. When protestors in Sunset Park went to Industry City both to reaffirm their intent to stop their proposed rezoning and to support frontline workers who were needlessly exposed to Coronavirus, they hung a banner on the main courtyard gates. The photo of the banner itself is an interesting visual image, leaving no way to tell who, exactly, was involved. During the Queer Liberation March, the Stonewall Inn (the site of the uprising that gave way to pride) was adorned with a banner reading “Pride Is a Riot #BLM.” The image, along with the large black balloons stating “we’re not free until everybody’s free” tell a story of that march that includes no identifiable people. Likewise, the first wave of protests in Manhattan and Brooklyn left significant graffiti behind. This is usually cleaned off within days, if not hours, but likewise tells part of the story of rage. The last six photos in this section show this graffiti as part of that story. Three of them include an identifiable person, but it’s unclear if that person was part of any march or action or if they were simply walking by. Another shows a police officer, and any time is a good time to point a camera at a cop.

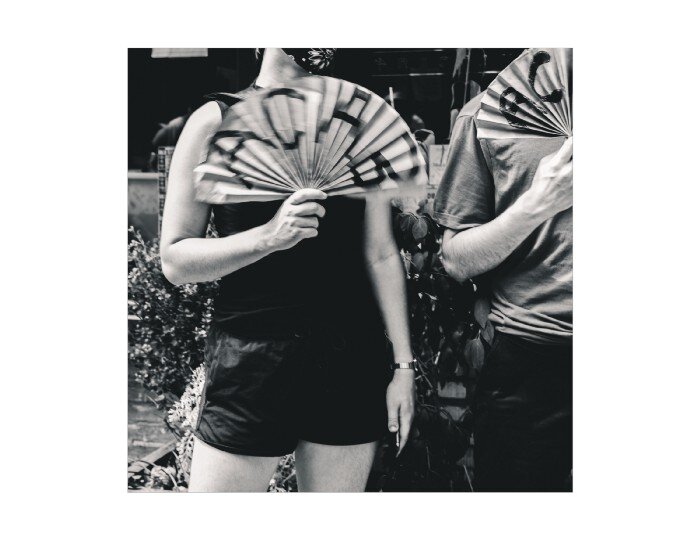

Sometimes, it’s worthwhile to include a person in an unidentifiable way. The first photo shows a person waving a red, black, and green flag at a recent protest. Both the location of the protests and the identity of the person are hidden, offering them some level of protection. In the second photo, two people have anti-police slogans written on their fans. Identifiable marks are cropped out and their clothing is fairly generic. Again, this photo could have been taken at any of a variety of protests.

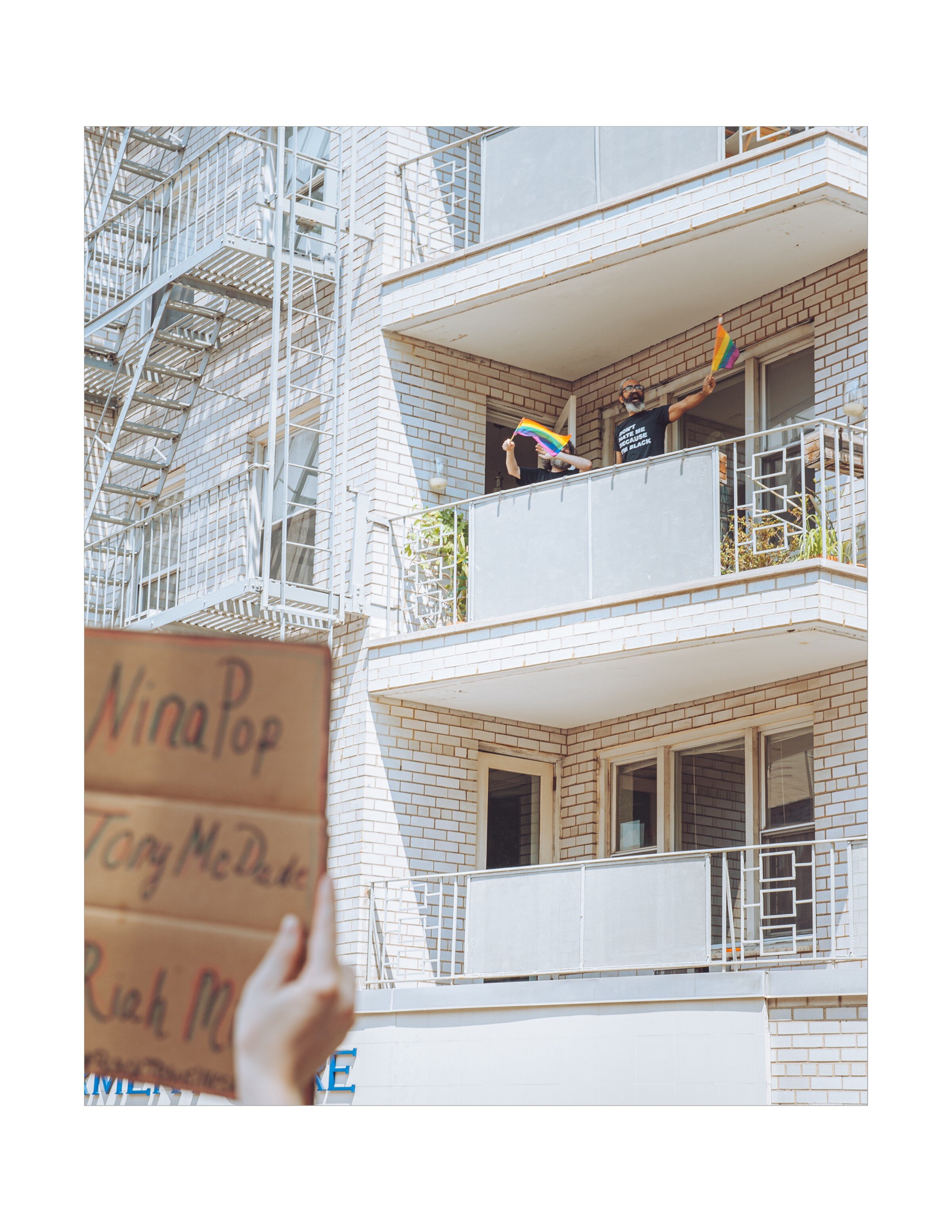

Finally, there are times when it’s important to show people but doing so requires a level of safety and recognition of what’s happening. In the first photo, protestors are shown entering the plaza at Barclays Center in Brooklyn. This photo was not published until well after the fact and when it was clear that police would not be looking for people who attended this protest. Without metadata and separated from the context of an individual action, it shows the size of the crowd without tying them to a single event. The second photo shows people not involved in the protest showing their support from their balcony. The exact location is not identifiable and the people in the photo are not directly linked to the protest below. The final image shows Jamel Floyd’s father giving an emotional speech to a crowd of supporters in front of the Metropolitan Detention Center in Brooklyn. The family were at the center of this activity and their presence was a known quantity, a shallow depth of field and the angle of the photograph were used to obscure the faces and identifying features of others.

I want to conclude with some personal dos and don’ts of photographing protests.

DO

· Use your skills and knowledge to tell important stories.

· Support and provide space for BIPOC photographers to tell their own stories.

· Photograph cops and suspected white supremacists.

· Remove all metadata associated with your pictures.

· Put some time between taking the photo and putting it online somewhere.

· Make every effort to protect the identities of the people in your photographs through creative editing and cropping, spatial and temporal dislocation, not needlessly photographing their faces.

DON’T

· Talk to or share photographs with police or FBI agents.

· Photograph illegal activities in progress.

· Take photos if you aren’t sure you can protect the people in them.

· Put people in harm’s way through your photography.

· Tag people or specific locations in your photos.

· Put aesthetics over lives.

Finally, remember that no photo — regardless of its aesthetic value — is worth a person’s life or freedom.